As part of our continuing effort towards thought leadership, McManus & Associates recently presented The Wall Street Journal with our impressions on the newest estate planning paradigm. The firm’s ideas helped shape a comprehensive, informative cover story in the Weekend Investor by well-versed Reporter Laura Saunders. The article, titled “The New Rules of Estate Planning,” also highlighted the Grevatt Family, one of our clients, for whom we employed a smart strategy in today’s environment.

The article is based on the reality that, for many families—generally individuals with less than $5 million in assets and couples with less than $10 million—the focus is now on minimizing capital-gains taxes and state levies. As pointed out by Saunders:

Finally, last year, Congress set the top estate-and-gift-tax rate at 40% and raised the exemption to $5 million per person, adjusted for inflation. It now stands at $5.34 million and is expected to rise to $5.43 million next year. Lawmakers also changed the rules so that couples don’t need trusts to get their full break from Uncle Sam.

Even though many people won’t owe estate tax, their choices about which assets to hold until death will greatly impact how much they pay in capital gains. Today, strategy is critical because the top federal rate on long-term gains is two-thirds higher than in 2012 at nearly 24%.

From the article:

The high exemption also is prompting changes in gift strategies and trusts, says John O. McManus, an estate lawyer in New York.

Sharing with readers how to capture capital-gains savings, Saunders highlights a provision of federal code dubbed the “step-up” that cancels the long-term capital-gains tax on assets that a taxpayer holds until death. “The step-up automatically raises the owner’s cost basis for such assets—the starting point for measuring a taxable gain—to its full market value as of the date of death,” she writes. To add color to this estate planning opportunity, Saunders features a real-life step-up strategy employed by McManus. From the story:

The new focus on the step-up prompted Ren Grevatt, now 94 years old, to do an about-face in his estate plan. For years, says his son Jonathan, who helps his father with his affairs, planners suggested that the father give his children the family’s beloved seven-bedroom Vermont farmhouse to avoid estate taxes that could have forced a sale.Now Mr. Grevatt plans to keep the house until he dies. He and his 87-year-old wife, who live in New Jersey, bought it for less than $100,000 in the 1960s, shortly before he became a publicist for such rock groups as the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin and the Who. The house, which is in prime ski country with views of two lakes, has appreciated greatly.As the parents’ estates will total less than $10 million together, no federal estate tax will be due. By holding on to the house, however, the parents will enable their children to inherit the property at its current market value—and skip capital-gains tax of up to 24% on decades of appreciation.“I’m glad my father didn’t get around to giving us the house,” says the younger Mr. Grevatt.

Near the end of the article, Saunders summarizes:

Given that the top federal rate on long-term capital gains is nearly 24%, compared with 15% a few years ago, the best course for people who won’t owe estate tax is often to forgo the gift and wait for the step-up, experts say. That is why Mr. Grevatt and his siblings were relieved their father never gave his children the Vermont property outright.

Saunders also sheds light on an “estate trust”, which puts complex moves to work in order to provide a double step-up on a highly appreciated asset to a married couple after the first spouse dies. McManus commented on the approach:

“This strategy provides flexibility by enabling the surviving spouse to sell the asset sooner,” says Mr. McManus, the New York lawyer, who advised the Grevatts.

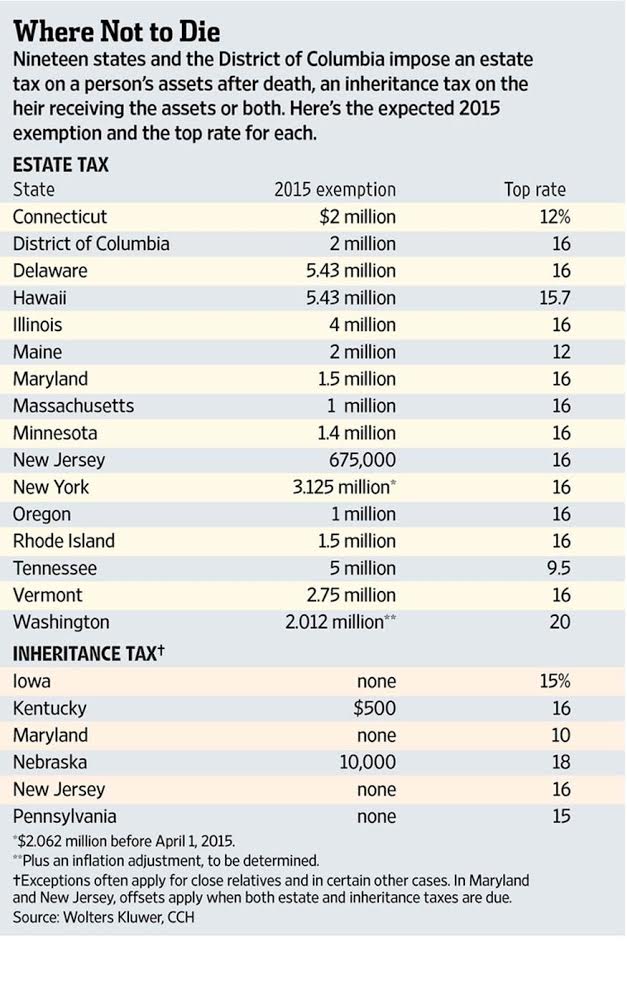

Included with the comprehensive article is a helpful chart showing amounts for estate tax on the assets of people who die, and inheritance tax on those receiving the assets, levied by nineteen states and the District of Columbia. Take a look:

To read Laura Saunders’ full article for the Journal’s Tax Report, click here.

⟩

⟩ ⟩

⟩ ⟩

⟩ ⟩

⟩ ⟩

⟩ ⟩

⟩